Johnny I hardly knew ye

| AKA | Johnnie I hardly know you (and other variations on the spelling) |

| First published | 1867 |

| Lyrics | JB Geoghegan | Music | Louis Lambert? Trad? | Roud Index | RN3137 |

| Music Hall performers | Sam Torr, Harry Liston, Tom Bass, George Beauchamp |

| Folk performances | Source singers O Fearghail, Seamus 1937/38 Ireland : Co. Cork Wareham, Leeland 1978 Canada : Newfoundland Wareham, W. W. 1979 Canada : Newfoundland Modern Performances Tommy Makem, Clancy Brothers, Joan Baez Many more! |

Johnny I hardly knew you From JB Geoghegan's 1867 Sheet Music While on the road to old Athy, A-hoo! A-hoo! While on the road to old Athy, A-hoo! A-hoo! While on the road to old Athy, The harvest moon was in the sky; I heard a dolorous damsel cry - Och! Johnny, I hardly know ye. Wid drums and guns and guns and drums The enemy fairly slew ye; My darling dear, you look so queer - Och! Johnny, I hardly know ye. Where is your nose, ye pitiful crow? A-hoo! A-hoo! Where is your nose, ye pitiful crow? A-hoo! A-hoo! Where is your nose, Ye had it when going to scatter the foe, The loss of it has disfigured you so – Och! Johnny, I hardly know ye. Where is your eye, that looked so wild? A-hoo! A-hoo! Where is your eye, that looked so wild? A-hoo! A-hoo! Where is your eye, that looked so wild? When my pour heart ye first beguiled Why did ye skedaddle from me and the child Och! Johnny, I hardly know ye. It broke my heart to see you sail, A-hoo! A-hoo! It broke my heart to see you sail, A-hoo! A-hoo! It broke my heart to see you sail, And seeing ye here has raised a wail – The cut of your head would embellish a tale - Och! Johnny, I hardly know ye. Where are the legs wid which ye run, A-hoo! A-hoo! Where are the legs wid which ye run, A-hoo! A-hoo! Where are the legs wid which ye run, When first ye went to shoulder a gun I fear your dancing days are done - Och! Johnny, I hardly know ye. Ye’s haven’t an arm, ye’s haven’t a leg, A-hoo! A-hoo! Ye’s haven’t an arm, ye’s haven’t a leg, A-hoo! A-hoo! Ye’s haven’t an arm, ye’s haven’t a leg, You’re a noseless, eyeless, chickenless egg, Ye’ll have to be put in a bowl to beg Och! Johnny, I hardly know ye. But sad as it is to see you so, A-hoo! A-hoo! But sad as it is to see you so, A-hoo! A-hoo! But sad as it is to see you so, And to think of you now as an object of woe, Your Peggy will still keep ye as her Beau, Though, Johnny, she hardly knew ye.

[Updated November 2024.]

This song is closely related to When Johnny comes marching home (RN6673): both were widely sung in the Britain and Ireland in the 1860s and both were extremely popular on both sides of the Atlantic. The balance of probability seems to be that the broadly pro-war version, When Johnny… was the original, and that Johnny we hardly knew you is a parody of it. They are sung to the same tune, which seems to draw on earlier, perhaps Irish, melodies.

The earliest reports of When Johnny comes marching home (RN6673) being sung on stage in Britain or Ireland that I can find are in 1865, in the repertoire of the blackface entertainers The Christy Minstrels. The words appear in the US publication O’Hooley’s Opera House Songster in 1864, and sheet music for a march version in 1863, but is quite likely have been around a few years before that.

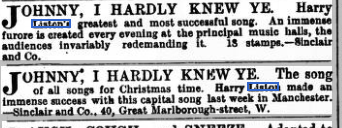

A number of parodies of When Johnny Comes seemed to have been in circulation in the mid 1860s, but the first report I can find of Johnny we hardly knew you being sung on stage in Britain or Ireland are in late 1866:

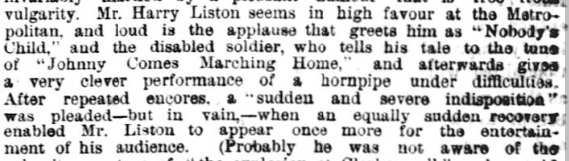

Later that year Liston was described performing at London’s Metropolitan music hall, telling the tale of a disabled soldier to the tune of Johnny Comes Marching Home:

This seems to be a reasonably clear indication that in December 1867 Liston was singing the Johnny We Hardly Knew You to the tune of the earlier song When Johnny Comes Marching Home – assuming he didn’t have another song about a disabled soldier. (It is interesting that there were earlier reports of Liston having some success with When Johnny Comes Marching Home – The Era, 13 Aug 1865)

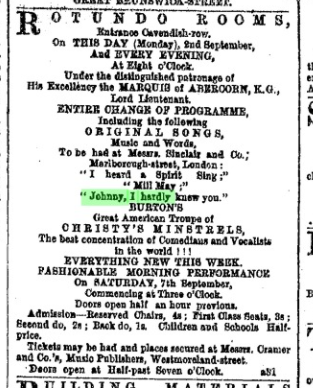

The Freeman’s Journal (Dublin) also carried advertisements for Johnny We Hardly … being sung by The Christie Minstrels late in 1867:

The words for Johnny we hardly knew you were written by Joseph Geoghegan, long-time master of ceremonies at the Star and Museum Music Hall in Bolton in the late 19th century. (He may well have also drawn on elements of an older song John Anderson My Joe, Roud 16967.) Geoghegan was responsible for writing a number of songs which entered the folk tradition, including the Sea Shanty 10 Thousand Miles Away.

The British Library catalogue has an entry Johnny, I hardly know you (Song begins “While on the road”) by Joseph B Geoghegan, published in London in 1867. This is the earliest confirmed date that I can find of this song appearing in print. The earliest that I can find this song appearing in print in America is in Henry De Marsan’s Singer’s Journal in 1869. Thanks go to Bryony Mitchell for sending me a scan of this sheet music, which was used as a source for the original lyrics given above.

In the late 1860s and throughout the 1870s the song was widely advertised as part of Harry Liston‘s repertoire.

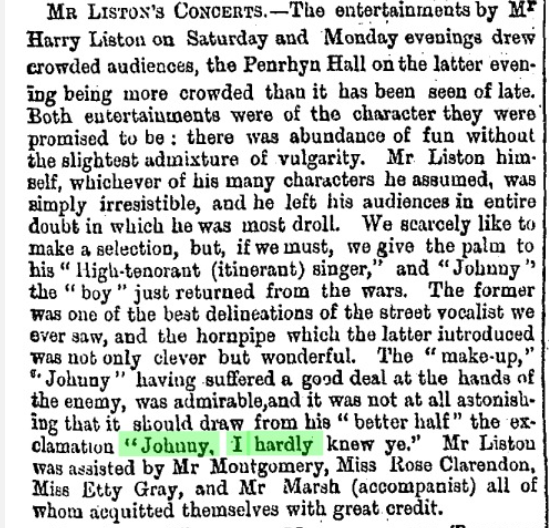

Johnny is another Victorian song written in “stage Irish” – drawing on Irish stereotypes for comedic effect. Contemporary audiences, both in Ireland and England are reported to have found it hilarious, and this description of a performance by Harry Liston’s concert party in North Wales suggests that Liston was definitely “playing for laughs”:

Johnny we hardly knew you appears uncredited in numerous broadsides and songbooks in Britain, Ireland and the United States, with some variation in verses.

Still to come: the story of how Johnny we hardly knew you ruined a politician’s life… When I’ve got time…

Post Script: Since writing the original version of this page I have come across the booklet: “The Best Anti-war Song ever written” by Jonathan Lighter. It’s an interesting article, and he goes into much more detail of the later history of the song, but the story of its origins as a comic song written by Geoghegan for the Halls is broadly as outlined here. I enjoyed reading the piece, but at times I was worried that the author seems to be implying that all subsequent leftist and pacifist folksingers have somehow got it “wrong” in seeing this as a vehicle for powerful anti-war sentiment. I think what is interesting is how the meaning of songs (and other art) can change over time and what this tells us about ourselves and our society. It seems to me that songs change both as a result of changes performers make in the words and music, and changes in the way that listeners hear them. It’s certainly the case that what Victorian audience found hilarious, would not necessarily amuse modern ears… Speaking personally, knowing that this song was originally written to amuse does not undermine its ability, in the right hands, to move this leftist, pacifist folkie.

Sources:

- On the origins of both songs: Mudcat.org

- Lyrics: JB Geoghegan Sheet Music courtesy Bryony Mitchell

- When Johnny Comes Marching Home in Levy sheet music collection

- Poole: Music Hall in Bolton

- British Library catalogue entry.

- British Library Newspapers (various dates)

- See also JB Geoghegan’s Facebook Page

- Jonathan Lighter, “The Best Anti-war Song ever written” Loomis House Press 2012

Joan Baez sings